Google Earth for the brain?

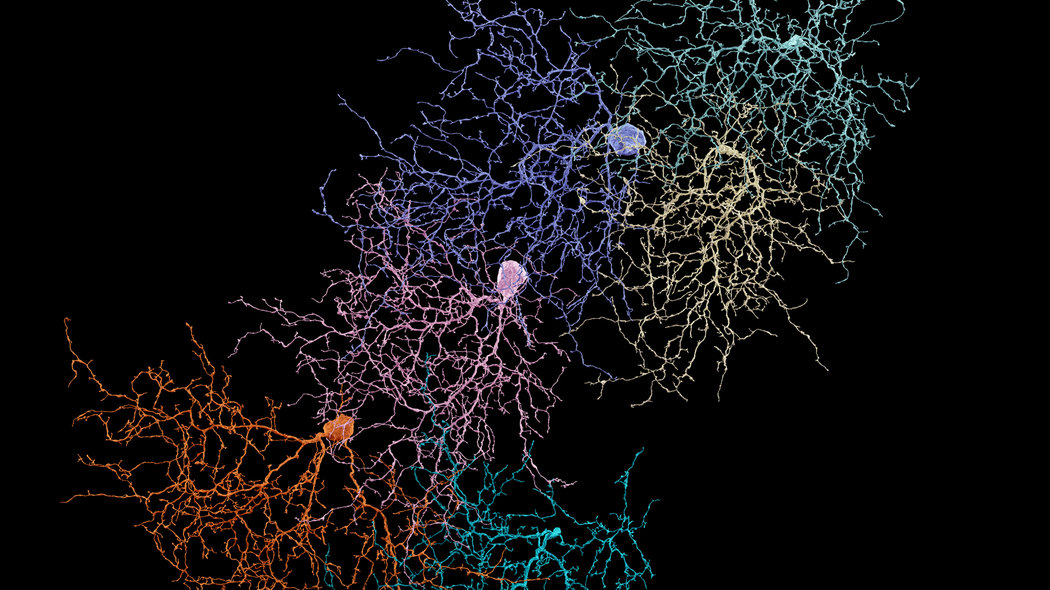

New York Times feature: Scientists combine high-resolution brain-image analysis with collaborative computer gaming in an attempt to map the totality of the human brain in a wiring diagram of all 100 trillion neuro-connections.

Since 2005, neuroscientist Sebastian Seung has spearheaded a comprehensive study of the human brain, which aims to map the entirety of neural connections in the brain. To entirely map the human “connectome” (all the neural connections) is a herculean task, far greater than the genome, but even though completion of a fruit fly connectome mapping is not expected to be completed for at least 10 years, Seung and his team are confident that a complete map of the brain is indeed possible. With the help of a collaborative online computer game, “EyeWire”, which collects data from players, individually tracing neuronal wiring in the retina of a mouse’s eye, processed by artificial intelligence and ‘deep learning’, he hopes to enlist a massive online community in brain mapping, hopefully one day assembling a complete map of the human consciousness.

Gareth Cook, author of the feature in The New York Times, interestingly comments on this mapping process with a brief note on Argentinian writer and literary critic Jorge Luis Borges’ text fragment, On Exactitude in Science (1946), in which Borges envisions an “Art of Cartography”, which has “attained such Perfection that the map of a single province occupied the entirety of a City.”, and indeed consequently a map of “the Empire” in 1:1, “which coincided point for point with it.”. Such an exhaustively comprehensive mapping indeed seems absurd and pointless, because what is a map if not a compacted visualization of complex landscapes? But it may in fact be exactly what faces connectome mappers worldwide, as the billions and billions of neurons wait to be extricated, quantified and made navigable in a database and indeed map form, which will require massive computer power and coding complexity. Perhaps the brain is simply too complex to be ‘mapped’, but, as recent decades have made quite clear, with near-exponential advances in computer technology on a yearly basis, it may just be a question of time. Or it may be a case of Sisyphus pushing his stone…

The map of the connectome has indeed “hardly left the starting line”, partly due to inadequate funding, but perhaps also because of the massive moral implications associated with quantifying the human brain. Indeed, as Seung argues, mapping a person’s brain may be likened to “capture a person’s very essence: every memory, every skill, every passion.”, and may, in the far away future to be sure, also allow scientists to reanimate an entire consciousness, post mortem, in database form. What would the philosophical implications indeed be, if the substantiality of an individual would simply become downloadable and digitally tractable data? And could a database consciousness be coaxed into spontaneous artistic production? No doubt questions for the future, but interesting still…

A Google Earth for the human brain, “weaving together many different kinds of maps, across many scales, allowing scientists to behold an entire brain and then zoom in to see the firing of a single neuron” would certainly spark a radical rethinking of what it means to be human and to be conscious, just as the first lunar images of the earth sparked reevaluations of human culture in the dawn of globalization.

This reevaluation will certainly be a task for the arts. The posthuman vision of digital consciousness has indeed been a hot topic in the science fiction films of the late twentieth century. And is literature not, at least in cases involving the stream-of-consciousness narrative technique, a codified consciousness, communicable from material book to human understanding; readable, palpable and quantifiable in language?

Read the New York Times feature here